Time for a diversion, topic-wise.

Once folks reach a certain stage in their lives, the time invariably comes when you decide you want to move from hanging posters (framed or otherwise) on your walls to cutting a cheque for something original.

Over the years, some of my industry confreres have asked me for advice about how they should tackle “getting started in the Art World.” How much should they spend on a piece, which dealers to visit, what to read, how to manage different tastes with your partner or team, navigating the advice of the Interior Designers who come and go through your life, how to know that you’re on the right track once you start buying stuff...all natural and appropriate questions. (This post won’t be very relevant to younger members of our industry, given the financial hurdle they need to scale before they can enter the housing market in far too many North American cities.)

The walls at Wellington Financial LP were filled with the works of various Canadian and international artists, which was both fun for me on the acquisition front, but also gave our entrepreneurial guests something more interesting and unique to look at than, say, posters of rowing skulls entitled “TEAMWORK.”

Our old firm sponsored the Canadian Art Foundation for many years, among other charities and causes, which was a fruitful way to support emerging artists and younger Art Dealers as they were making a name for themselves. That involvement led to many of the original pieces on our walls…which might have left people with the impression that I knew what I was doing on the collecting front. Not so. There was no acquisition strategy beyond buying images with an “Industrial” feel, which I thought made sense for a firm that financed a wide range of companies.

In the wake of a gratifying trip to see the Museum Of European Photography’s Irving Penn show in Deauville, a beautiful town on the Normandy coast, I thought I’d sketch out the advice that I’ve given over the last decade. If it was only political topics, you might get the wrong impression. ;-)

(photo credit: MBM)

Be forewarned that this will be simplistic, long and a bit more “financial” than some of my Art World friends might like. There are folks who hate it when I look at the relative values (ie. cost to acquire) of their artist’s works, which apparently means that you’re thinking with your head and not your heart. Folks with any Bay/Wall Street experience know what that’s all about: if you can get the would-be buyer to become emotionally connected to something, they’ll be more likely to pay up! Which means a higher commission for the dealer.

Please note that I’ve never taken a single course in Art History (my sister, Dr. Alison McQueen, is the published Art Historian; lecturing at Universities and Museums the world over regarding her areas of expertise). And while I’ve read a bunch, every art history Grad student and dealer in North America would have more training, insight, knowledge and expertise in their pinky finger than I have gleaned or retained over the decades. What I can arm you with is a few guideposts about where to start your journey, how to protect yourself from being asked to unwittingly spend $25,000 or $50,000 on something merely because it matches a rug or couch, and how to navigate a sector where it’s been said that “the only people who make money in the Art World are the shipping companies.” Which I find funny given that gallery owners and auction houses take between 20-50% of the gross proceeds of every sale. Compare that to the profit margins at a grocery store.

For ease of use, I’ll tackle things in buckets.

VIEWING - WHERE TO START part one:

Public Art Galleries & Museums — most towns and universities of any size have a gallery tucked away somewhere, and you might as well begin your lifelong Art journey there. Although the vast majority of publicly-owned art collections are actually in storage, places like the Vancouver Art Gallery, Whitney Museum, Rijksmuseum, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the AGO, the Getty, Frida Kahlo Museum, Beaverbrook, La Bourse de Commerce, Met, MOMA, Prado, Montmartre…have all assembled world-class permanent collections. Make the effort to view them whenever you can, even on vacation with your family, as you’ll start to see some familiar themes trickle down from one artist to another over the decades. While many of the works at these public galleries will be priceless, or perhaps not your taste (you may not share a love for Flemish paintings with a 16th century Spanish ruler), it’s still a good use of your time to see as many representations and genres as is feasible while you get a sense of what you like/love/yawn at.

For the venture folks, you’re particularly blessed as SF and LA are two cities that you likely have reason to travel to from time-to-time and can squeeze a one-hour museum visit in-between meetings: SF MOMA, the de Young, Legion of Honor and The Getty all make this easy.

If you don’t mind the two-dimensional approach, museums such as MoMA have posted a large portion of their collection online — >100,000 different works, so far. Cheaper and less hassle than a weekend in New York.

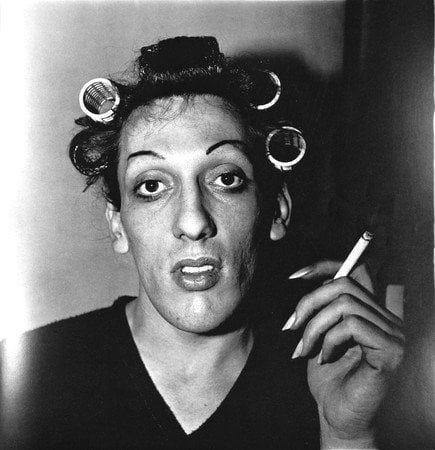

If you aren’t able to travel very far but you’re patient, you are still going to have the good fortune of seeing touring exhibitions in person when they come to your local museum(s). At the AGO for example, there are currently twelve different shows on view, above and beyond the permanent rooms showcasing masterpieces such as Ken Thomson’s legendary Group of Seven collection, for example. The AGO’s world-class Diane Arbus collection is touring the world, with a stop in Calgary, which speaks to how collaborative many globally-minded museums are.

This is to your benefit, both ways, even if these museums have been historically financed by donations from “the Patriarchy.”

(A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, New York City, 1966, by Diane Arbus)

VIEWING - WHERE TO START part two:

Private Art Galleries — most cities of any size will have local galleries, run by entrepreneurs, and you’ll surely be able to find at least one for every price point and financial stage of your life. Although you can access hundreds of international galleries online, your local ones are the best place to begin to be exposed to a few of the hundreds of thousands of living artists the world over. And while you might find auction-quality stuff at a local dealer, it’s more than likely that what you’ll see in any particular neighbourhood gallery is a function of the owner’s relationships with individual artists, their personal reputation, specific areas of knowledge/interest/success, and so forth. It could be one or more of Contemporary, photography, oil paintings, Pop, sculpture, abstract, NFTs (yuck), and so on.

These operations are usually filled with extremely talented people, so sign-up for their mailing lists, attend their shows and see if you can rope them into helping you on your life journey as you build your personal knowledge base.

ACQUIRING - WHERE TO START:

Whether it be at auction (in person or online), an estate sale, or a local or distant private gallery, the options will feel endless because they are. Importing art is certainly doable, but in your early years you’ll likely want to see pieces in-person before pulling the trigger. Which means buying local.

For me, an early lesson about how “gallery art” is priced (beyond the most obvious: what the market will bear) came when I asked a dealer if they liked a work by a certain artist. Her reply got to the heart of the matter: “his son printed that stuff like wallpaper.” The hint was clear: if there are so many versions (copies/editions) of the piece in question, the value (maybe US$2-4k in this case) is unlikely to ever go up. Particularly if there are no records of how many prints were made.

That might be just fine, provided that you had no expectation of financial gain. Art is an asset in many cases, but that doesn’t necessarily make it an “investment.” Some pieces I acquired 10 years ago are flat, and that’s pre-transaction costs and insuring them over the ten year period, while others might be up 50% over five years.

If your artist of interest is no longer alive, you might be able to quantify how many different works were produced during her/his lifetime and gauge accordingly (assuming that no one is still printing the negatives in the case of photographs).

Don’t assume that a high or a low price, however, determines whether or not what you’re buying is actually unique and worth collecting. There is no wrong answer if you love it! But, unless you’re renowned collector Francois Pinault, I doubt that you have a bottomless chequebook.

Toronto’s Art Interiors Gallery was started in Forest Hill Village many years ago with the idea that original art should be more “accessible” to individuals, and the owners undertook to have a price ceiling of $5,000/work. Over in Yorkville, you might pay gladly more than $5,000 just in tax for something by “Mr. Brainwash” at Taglialatella Gallery or Galerie de Bellefeuille. His works are incredibly popular right now, and you’re going to come across them in high end homes in places such as Aspen and Palm Beach. Many of his pieces are very similar, even if they’re original in nature — there’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s something you’ve got to be comfortable with. I have one myself, as that particular work echoes another piece by a different artist hanging nearby in our house.

Go have a look at his lively stuff one day and join the “Is he a poor man’s Banksy? And does it matter?” debate.

(With All My Love, date unknown, Mr. Brainwash)

And then get yourself to MOCO in Amsterdam (KLM is far cheaper than AC) to see a stunning group of Banksy’s — many of which are on loan from private collections; taking your knowledge base one step further. That MOCO is one of Eddie Vedder’s favourite museums has no bearing on this advice whatsoever, but feel free to drop his name when your friends ask you why you chose that particular destination (the world’s best Rembrandt, Vermeer and Van Gogh combo collection is also nearby) for a summer art tour.

Some (most?) successful dealers develop exclusive local relationships with higher profile living artists, which is the case with Douglas Coupland and Toronto’s Daniel Faria, for example. Or Paul Rousso and Laura Rathe Fine Art in Texas. This makes your life easier in the event you become a fan of a specific artist — the gallery owner might serve as your tour guide / teacher for life.

(Print Implosion, by Paul Rousso)

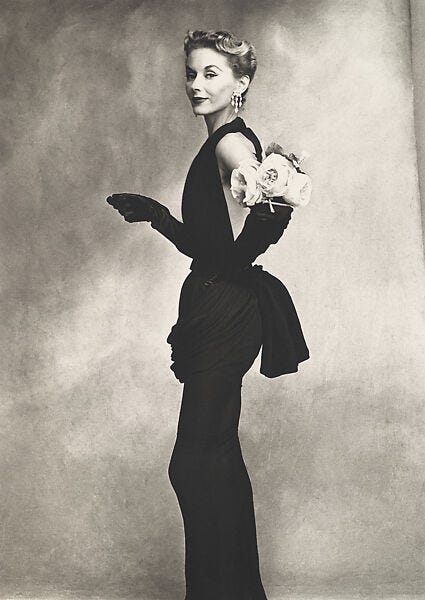

That’s certainly how I came to know and love Irving Penn. A walk around Jane Corkin’s old gallery on John Street ~25 years ago (before it moved to Toronto’s Distillery District) was my introduction to his work. There were dozens of different pieces on display by a variety of artists, but I stopped and stared at this one for the longest time.

(Woman with Roses {Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in Lafaurie Dress}, Paris, 1950, by Irving Penn)

“You have good taste,” said Ms. Corkin, who it turned out just happened to be one of the most respected vintage photography dealers on the planet. “That’s the most expensive picture in the show.” Just my luck. As a former professional newsphotographer, I suppose it shouldn’t come as a surprise that I might be drawn to the genre. And there’s so much to love across this underappreciated discipline: Berenice Abbott, Ansel Adams, Diane Arbus, William Eggleston, Robert Frank, Dorothea Lange, Danny Lyon, Sally Mann, Sebastião Salgado, Hank Willis Thomas, George Tice….

The global auction houses will all let you set-up online accounts, enter your areas of interest, and you can be sure that they’ll email you every time there’s a relevant upcoming auction. This is a passive way of learning, and even acquiring, as soon as the mood strikes.

Not every local gallery will feature artists that are going to make the cut of a Christie’s, Phillips or Sotheby’s auction; few might, in fact. This won’t surprise you, and it doesn’t speak to the quality of the work. That said, if a museum has intentionally acquired a work by someone you’re keen on, that’s obviously a good datapoint.

Each of us “likes what we like,” and the fact that you might love something at the gallery at the end of the street by an artist that no other dealer in Canada or the USA is carrying is not a reason to second guess yourself.

It wasn’t that long ago that $250 would get you a Lawren Harris at Toronto’s Roberts Art Gallery; good luck buying that same small oil for $100,000 today. It may well be that you might be discovering a future global star, as a family friend of mine did when she bought three Andy Warhol originals at a gallery in SoHo in the early 1960s. Warhol wasn’t an absolute nobody in 1963, but that fact that you could buy these images at a gallery for less than 1/2000th of their current value speaks to the opportunity for DIY hunting/collecting.

For most of us, that’s not going to happen. Which means, in the event you might ever want to sell the work, we have to be careful conscious about the price point for what I’ll call “as yet undiscovered” artists. In a world where an Ikea sectional couch costs $2,500, there might be merit in spending $5,000 or $10,000 on a picture for your living room on the basis that you’ll have the artwork for life, unlike that couch.

That said, $10,000 is a decent chunk of change for a single piece (even if the framing cost $750). If you love oils as compared to watercolours or photographs, there will be an upward impact on price, along with the size of the image and the macroeconomic backdrop at the time. This is where the auction houses come in handy if you pay attention to an artist or discipline over a period of time.

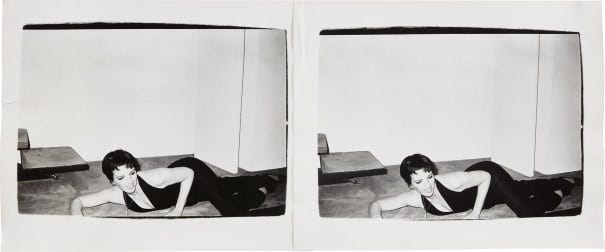

If you had US$5,000 as a budget for a single piece at a Toronto or NYC auction, with or without the hammer (the “premium” or commish that the auction house adds to whatever you paid), you just might be able to acquire something that makes the cut on the global market. I just scanned a few auction sites and found this Warhol, which is estimated by Phillips to go for US$2-3,000 on June 21st.

(Liza Minnelli at Halston's House, 1980, by Andy Warhol)

Is it “quality” at that price? Of course. Are you ok with the fact that there are 249 others around the world, just like yours? Or that it’s a “Silver Gelatin” print, which might not last as long as one printed with a platinum solution? It’s also possible that you’re one of those people who don’t think photographs are “art;” it’s opinions such as that which makes this part of your non-work life so personal.

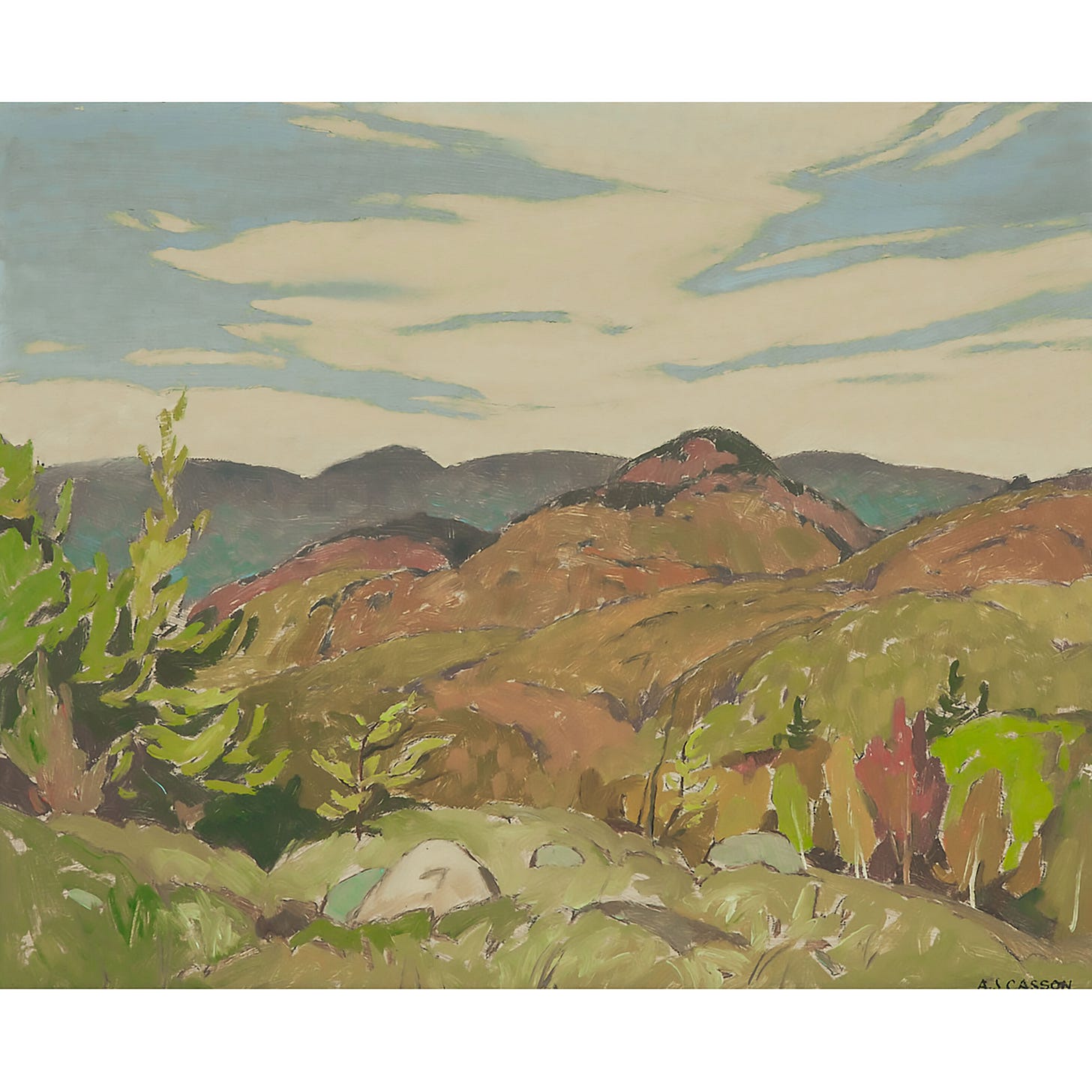

If Canadian art is more your tase, there was a slew of Group of Seven’s or a Jack Bush available a few days ago for between $20-25k each (inc. premium) via an extended online Waddington’s auction. Fifteen years ago, they might have gone for $10-15,000, which means i) you’re not going to make a great IRR on a small Group of Seven, and ii) collecting tastes are evolving, even for iconic segments of Canadian Art.

(SEPTEMBER NEAR BARRY'S BAY, 1964, by A.J. Casson)

I started my own auction odyssey in May 1996, at the former Park Plaza Hotel. With three mortgages at the time, I’m not sure I was a viable bidder, but I sat there with the catalogue and hoped to soak up what I could. According to my contemporaneous notes, $5,500 plus hammer would’ve secured you a nice little 10”x6” Lawren Harris via Sotheby’s Canada. That was long before comedian Steve Martin discovered him, of course! To have a sense of the world you’d be “in,” a stunning large Harris, from the collection of the late William P. Wilder, former President of Wood Gundy, WWII veteran and holder of the French Legion d’Honneur, realized ~$5 million not too long ago.

You can justify anything in the Art World, of course, and you definitely want to love it if you’re going to hang it in your home — whatever you pay. As for where and what to buy, that’s tougher, all things being equal. As a former Nesbitt Burns trader used to say: “whether it’s furniture or art, I want to know that if I ever have to sell it, I can bundle it off to Christie’s in New York and get a fair price.”

I’m a big fan of local dealers. They make art and artists accessible in most cases, and they’re all entrepreneurial risk-takers by nature. The kinds of people that venture folks and company founders are used to working with.

Yet, like the rest of us, they have a business to run. The rent is never cheap in the places where galleries tend to set-up, and every gallery requires a team of various experts to even have a chance of being successful. Given the nature of the business, few dealers can make a living selling artworks for less than a few thousand dollars a pop. Do the math on what an artist needs to earn to survive year-to-year, leaving aside the dealer’s overhead, and it all makes sense.

The trouble is when you get into the $40,000 range, say, which goes a long way at auction. The recent run-up in asset prices had an impact on many corners of the art world, as a bunch of bored people with no where to go and some unspent travel funds (or unrealized gains in the stock market) decided to buy art at online auctions. “People went crazy,” I’m told.

The peak auction prices ever paid for a Banksy just happened to coincide with Bitcoin’s peak, I can’t help but mention. Which also happened to overlap with the decision of some of the global auction houses to accept certain cryptocurrencies as payment. Next thing you know, guys were paying more than US$5 million for an original, shocking even the artist himself. It made total sense to me, mind you: if you rode Bitcoin from US$800 to US$65,000, swapping that bounty for something tangible — something recognizable, that you could admire — was entirely logical.

The COVID-era upward price excitement impacted the local art market, and perhaps not for the better. That a Warhol Marilyn Monroe print, which appeals to a global market, doubled in value during the pandemic isn’t an argument to raise a local artist’s work from, say, $7,500 to $15,000, in the absence of other factors. Or is it?

(Marilyn Monroe, from an edition of 250 screenprints, 1967, by Andy Warhol)

Regardless, you now can bring the “local galleries” of Provinces and countries into your life via the web: Artsy. Galleries from around the world regularly showcase some of their works on the site, and you could spend days tailoring your areas of interest into Artsy’s platform. This gives you more options, and ensures that you stay in touch with global price trends and tastes.

Give it a whirl.

As time passes, and your confidence and knowledge base grows, you’ll be ready when the time comes. There’s a saying that if you only buy art that you and your partner can agree upon, you’ll wind up with a “corporate” art collection. The thinking being that committees choose art at big companies, which dilutes the flair of any individual collector or passion. I don’t have an opinion on that, but what I do know is that if either of you “love” it, you should buy it. If you both “like” something, all the better.

Enjoy the ride.

MRM

Good post. We can work on changing your mind on digital assets / NFTs over time.

Mark: Incredible advice.

I have little understanding of how to value or collect art. You and I were trained as business valuators and deal makers. The best investment anyone can make today is Private Equity.

Please invite me to see your collection. I will bring some fine wine and cheese.

Mark Borkowski, pres.

Mercantile Mergers & Acquisitions Corp

1 King Street West, Suite 714

Toronto, Ontario

M5H1A1

(416) 368-8466 ext. 232

cel- (416) 531-4759

www.mercantilemergersacquisitions.com