The horror story of one former Community College Instructor

"The Colleges are aware of the situation with academic integrity surrounding a large cohort of the international student community and take no real action to put in place programs to halt it."

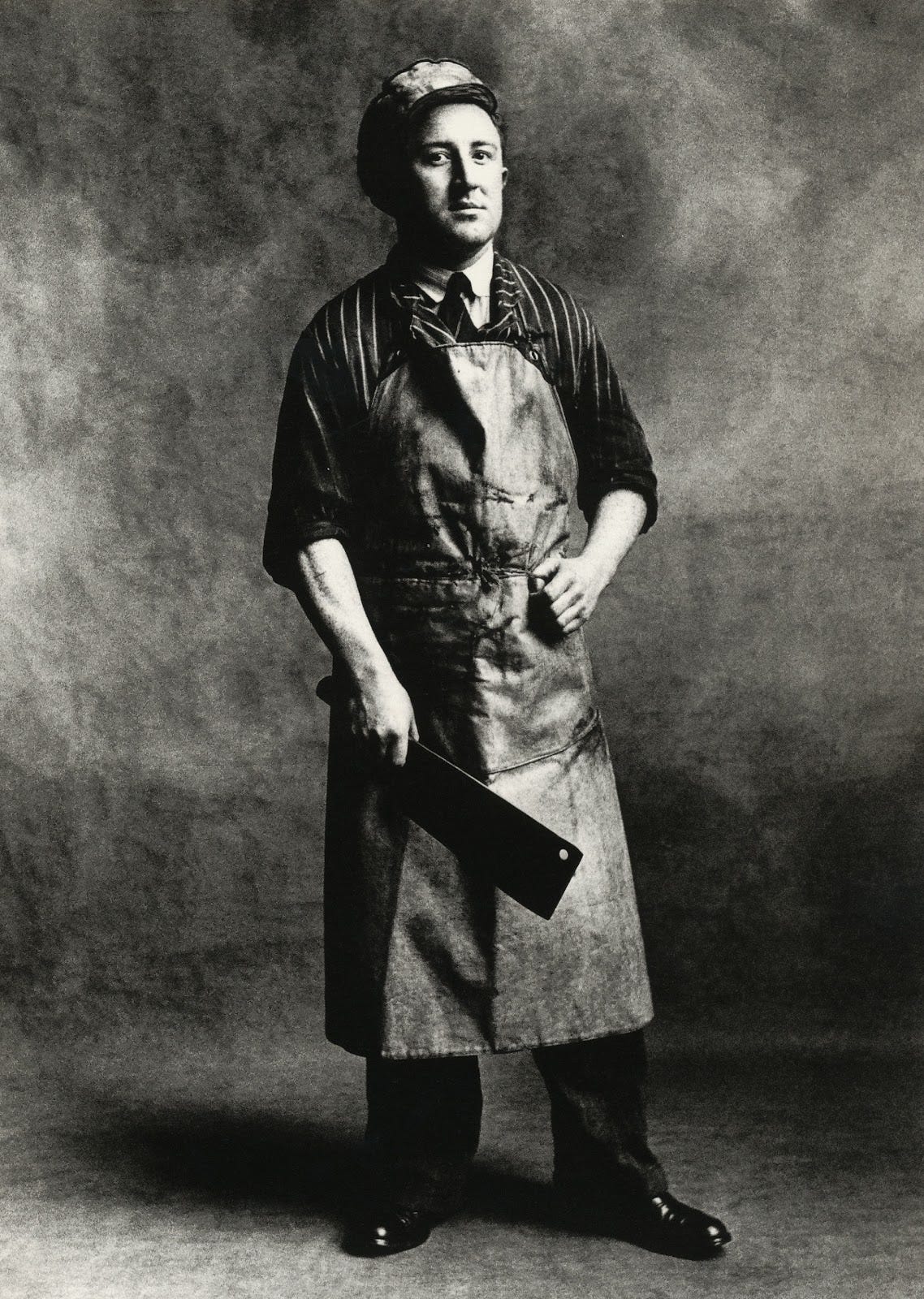

As part of my research for this week’s Toronto Star column (We should be taking a scalpel, not a machete, to the international student program), I spoke to an experienced business woman who had previously decided it might be both fun and rewarding to teach a Business course at an Ontario-based Community College. Although she quit in disgust before the end of Covid, I found her insights into the travails of our post-secondary system sufficiently compelling to share her experience and perspectives with you all via a Q&A format.

Q (MRM): What do you think was the genesis of the explosion of foreign students attending Community Colleges ?

A: It started out simply enough. The Community College sector was supplementing reduced payments from the Provincial Government and the inability to raise tuition fees for domestic students by opening their doors to more and more international students. They pay significantly more to take the same course, even though the College gives them no additional value relative to a student who was born around the corner. This tuition fee premium had started when I took my first contract faculty position seven years ago.

Q: In your experience, what brought these students to your classroom?

The timing was perfect for these Colleges, as the federal government created a new “pathway” for Permanent Residency (“PR”). If an individual completed a two-year accredited post-secondary program and worked in the field for a specified period of time (initially a year or 18 months as I recall) they would be “eligible” for their PR card. I was told that it was basically a given, that no one was denied PR provided they completed the program and subsequent work experience requirements. It was clear that any work would be sufficient for the “work in the field” component of the PR eligibility. For instance, following their two-year business diploma, an international student working at Tim Hortons or driving a truck would meet the requirements to gain Permanent Residency.

All Ontario Community Colleges (Conestoga, Humber, Mohawk, Sheridan, etc.) saw enrollment in any two-year program become extremely attractive to the PR-Seeking international student. I generally taught courses in the two-year Business program where 75-80% (maybe even higher) of the students were international with the goal of Permanent Residency. The diploma was viewed as a necessary step, but their motivation was not for the education that they had signed up to complete. I once taught a business communication class in a two-year Administrative Assistant course where there was a large portion of male international students. They had zero interest in the program, nor an ability to speak the English language in a manner that would allow them to be hired as an Administrative Assistant. It was merely a two-year program and it fit the bill for what they needed.

Q: What is the problem with allowing students to work while they’re here?

To begin with, the student visas that I dealt with gave these international students the right to work, and most seemed to need a job in Canada to pay for their meals and rent while they were studying in Canada. The type of international student that were interested in the study-to-PR pathway tended to be from one region of one Sub-continent country. There were international students from other countries, but the vast majority came from a specific area within this one Sub-continent country. These students were not wealthy, and I understood that many families leveraged agricultural land to afford the tuition for the courses in Canada.

Because the federal Immigration department granted them a student visa despite having an absurdly low level of funds available to them ($10,000?) to cover their expenses over their two-years in Canada, these students had to work. The student visa initially allowed for 20 hours of work, and I think over COVID it was increased to 30+ hours a week. I highly suspected that many of the students worked much, much more than the stipulated hours the Government mandates.

Unlike in the U.S.A., where foreign students are generally prohibited from working anywhere but on campus, our system was structured in a way that almost required these foreign students to work at some minimum wage job in our city.

Unfortunately, they had to work so much to afford to pay for their expenses, there was not much time to learn the material I was teaching, do assignments, or prepare for tests and exams.

Q: What were the key challenges?

Almost all of the international students I dealt with didn’t have sufficient savings or family financial support to cover their expenses without working. They would work any hours given to them. Their attention was not on schoolwork. They are working, trying to scrape together a life here, which led to constant absenteeism. They would show up for the final exam, maybe. Never hand in anything, or if they did it was plagiarized or a direct copy and paste from ChatGPT. They requested extension after extension. Cheating on in-person exams was crazy, talking, passing notes, hiding phones…. It was insanity.

This wasn’t with all of my international students. The problems were primarily with the students who didn’t have time to actually attend class, because they were so busy working some minimum wage job somewhere.

Q: You make it sound as though basic English was tough for many of your students

Many of the students I taught could hardly speak English, let alone write English. There was a requirement that to have their student visa approved, they needed to pass the TOEFL or IELTS English test. These tests are conducted abroad and the results provided to my College were likely fraudulent.

Our school wasn’t the only one that was duped. In 2018, Niagara College asked over 400 international students from India to retake their English language tests because of “inconsistencies” and their inability to complete their schoolwork. Every College professor that teaches in these programs know that the level of English is subpar, which has meant that overall classroom standards and expectations have dropped for everyone.

Q: Where does that leave the Community College Instructors?

The vast majority of Community College professors are contract faculty. I’d guess that in Ontario, up to 70% of Community College faculty are partial-load contract workers. We sign a contract each semester for a certain number of hours of teaching time. For instance, if I teach one class per semester I get paid three hours a week to “teach” that class; which would generate about $350 a week in income for me. Marking assignments, communication with students, etc. is included in that three hours.

As a contract faculty you are not paid for curriculum development or exam creation. You can augment or change things to fit your lessons, but you are given a course to teach, along with assessments.

Because there are so few fulltime faculty, many courses have not been structurally changed in many years. Exams and assignments are pretty close to the same each year. As a result, most of the multiple-choice exams are floating around on the Internet, most assignments have been done before, and every international student has access to most of the assessment materials in order to “get by.”

Given the compensation structure doesn’t cover your time “outside” of the three hours you might teach in that classroom each week, starting the process of dealing with academic dishonesty drops an already measly compensation level to almost nothing. The Colleges are aware of the situation with academic integrity surrounding a large cohort of the international student community and take no real action to put in place programs to halt it. As I was teaching more for the experience than the income, I would just give students zero if they got caught cheating and deal with the onslaught of emails pleading their case.

Q: How did all of this impact the classroom experience for the other students?

Fundamentally, the enormous increase in International students has negatively impacted some core diploma programs at Canadian Community colleges. Academic standards have been lowered, and some may argue that the value of the education for some of these courses has diminished.

It is highly demotivating to the other students. It was difficult to create a classroom dynamic that fosters a sense of excitement of the material being taught.

Q: Any parting thoughts?

This represents my experience instructing in the Community college sector. I would suggest that it would not be the same at the Universities. They are courting a very different kind of international student. I would expect a contract faculty in a University school of business would have a very different experience than I had as a contract faculty at my Community College.

I know I sound really harsh, I actually really liked most of my international students. I feel they were being exploited by a federal Immigration program that wasn’t being controlled, and a provincial government and College sector that was looking at their tuition to balance their budgets.

MRM

(note: this post, like all blogs, is an Opinion Piece)

(photo credit: Meat Carrier and Boner (A), London, 1950, by Irving Penn)