"Shadow Banks" are neither "banks" nor "shadowy"

Begging the question: why do so many influential folks promote the label?

Could there be anything more “free market” than two private companies agreeing, in the presence of their external legal counsel, to enter into a private loan transaction? What’s the role for a government in that scenario, when a Private Credit fund advances a loan to a private (or public) operating business? Beyond ensuring that the interest rate isn’t usury, which is long-defined in legislation, I just don’t see it.

According to one of my morning newspapers, the aforementioned private credit fund is a “shadow bank,” and should be “stress tested” just like a normal bank, so recommends a G&M columnist that I usually agree with. Apparently, private credit funds operate in the “darker corners” of the financial system, which, when you put it like that, sounds like a dirty business. The kind of thing that unschooled politicians and public officials should fear. The logic goes that while the recent Silicon Valley Bank (see prior representative post “In a matter of hours, decades of brilliance is undone at SVB” March 10-23), Credit Suisse and U.S. Regional bank crisis appears to be abating, Regulators have no idea what other risks are lurking in sectors that they currently don’t regulate.

Before we market participants decide if we need to regulate something, the first challenge is defining what a so-called “shadow bank” is. As a private credit fund has no deposit-taking function, it’s certainly can’t be a “bank.” It plays no role in the daily movement of money within the economy, and, no matter how large the sector gets, Joe/Jill Retail will have a modest direct exposure to the asset class — unlike the banking sector, which touches every individual in the industrialized world.

As I’ll outline shortly, none of Joe/Jill Retail’s investment exposure to the direct loan world will likely be unregulated, whether they’re members of a pension plan or hold a Corporate Loan ETF, for example.

When he was Governor of the Bank of Canada, Mark Carney would often refer to alleged growing risks in the “shadow banking” market. I once told him that the label itself was pejorative, and seemed geared to scare folks about risks to the financial system that just weren’t there. It’s only been a decade since that informal interaction, and while troubles at funds such as Bridging Finance and Third Eye have garnered media attention in Canada, you’d have a hard time naming a single systemic fear — let alone risk — that has arisen as a result of discrete challenges within the private debt market.

Mortgage Investment Corporations have grown over the years, but if the non-bank home mortgage market is dominated by government-guaranteed mortgages, it’s hard to comprehend how anything under the nose of the Federal government — having approved these firms as financial intermediaries — can be referred to as operating in the “darker corners” of the economy.

As for the performance of management and their Inspectors within a highly-regulated global bank market, the one that’s not functioning in the so-called shadows, there are plenty of members of U.S. Congress, as well as other observers — such as the Brookings Institution — who are convinced that things aren’t going great there:

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is a failure of supervision as well as regulation. The two terms are used interchangeably but are different concepts: Regulation is about creating rules, supervision enforcing them. Initial reactions to SVB’s failure focused on debating whether the Trump era deregulation caused the failure, ignoring the fundamental question of whether the rules that existed were being properly enforced. The answer is that they weren’t and that the Federal Reserve failed as a bank supervisor.

That’s not to say that the Private Credit world won’t get topsy-turvy down the road, but none of the folks who natter about “shadow banks” have effectively articulated what that would look like. And how that future turmoil would directly impact the financial system, writ large. And what benefits direct Supervision of a group of Private Credit funds would bring to prevent that turmoil from ever happening.

The allure of government regulation is different than the actual useful impact of same.

HSBC has been highly regulated for decades, but that didn’t stop the institution from reducing its anti-money laundering team, which apparently led to years of laundering money for Mexican drug cartels; while that episode eventually led to a US$1.9 billion fine, HSBC’s disinterest in AML wasn’t something that its U.S. bank regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, got too fussed about:

In this case, HSBC provided money-laundering services of more than $881 million to various drug cartels including Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel and Colombia’s Norte del Valle cartel. This included bulk movements of cash from the bank's Mexican unit to the U.S., with little or no oversight of the transactions. It also conducted transactions with Iran, removing references to the country in an effort to conceal them.2

Lacking in these instances is a corporate culture that prizes integrity. Enabling the business of drug running and state-sponsored terrorism in the pursuit of profit leads to dire societal consequences. Blame may be placed at the foot of the banks and regulators alike. In the former instance, inadequate anti-money laundering (AML) controls were principally at fault. In the latter, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) failed to crack down on HSBC's deficient implementation of controls.

Indeed, prior to 2010 when the OCC cited the bank for many AML deficiencies—including a huge backlog of unreviewed accounts and failure to file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs)—for the previous six years the agency failed to take any enforcement action against the bank.

My comfort in saying that Private Credit doesn’t offer unchecked systemic risk arises, in part, from understanding both the role that private credit plays in the economy, as well as its relatively modest size. The NBFI market certainly isn’t every “non-bank financial” in Canada, as that $1.71 trillion domestic sector referenced in The Globe & Mail would include mutual fund companies, such as AGF, investment dealers (think Raymond James Canada) and LifeCos, like Sun Life or Manulife.

While Sun Life does offer both direct and indirect lending, it’s already regulated by OSFI…the same federal body that oversees The Royal Bank of Canada — an actual bank. Raymond James Canada is regulated at least monthly by IIROC (not to mention the SEC via its parent Co.), like all investment dealers. The large Canadian mutual fund companies are carefully watched by the Ontario Securities Commission; and despite that close eye, recall that the OSC fined four of national firms $156 million for giving preferential treatment to their institutional clients at the expense of Joe/Jill Retail.

As for the private credit market, which my former firm Wellington Financial LP played in, the global asset class was recently estimated to be $1.5 trillion; that’s nothing to sneeze at, given the asset class didn’t really exist 20 years ago (beyond mezzanine and venture debt). You can imagine how small Canada’s slice is, relative to the country’s insurance and mutual fund players.

While the $2 billion AUM Bridging Finance may turn out to be a self-dealing fraud, there is plenty of evidence over too many decades that regulatory oversight doesn’t prevent bad behaviour by any firm, big or small. Nor does this oversight ensure that retail investors won’t lose money due to crappy investment strategies (see representative prior post “24 of 25 O'Leary Funds lost money in 2011” May 27-12). Investors appear to have been laid out in the Bridging case, but that’s a fundamental risk in any investment strategy — and nothing unique to the private debt market.

Which leaves us to consider the potential for systemic risk in the event a $5 or $10 billion debt fund failed. What might that look like? Who would hold that risk? And what would a failure of a large debt fund mean for the financial system? And how would that compare to the failure of Lehman Brothers, AIG, or Signature Bank?

I think about all of the steps that go into asset allocation, and the potential fallout that arises in the event that a regulated $100 billion Canadian pension plan allocates, say, 7.5% of its assets to 20 different funds in the private debt sector…and subsequently makes a poor choice of GPs.

What if 100% of that $375 million allocation to a $5 billion fund winds up eventually being worth zero, because some bad actors found a way to lose it all in some dramatic fashion? And what if that $5 billion fund had a $2 billion warehouse line with a dozen banks, who each did a poor job of managing which loan assets were within the approved collateral basket of the warehouse line? No bank wants to take a $200 million pasting on a leverage line, but relative to the size of the balance sheets of any particular money centre bank, a $200 million write-off is a drop in the bucket for Wells Fargo or BoA. And that only happens if the pension plans won’t honour their capital calls to pay off the warehouse line that was arranged for their benefit, and with their consent.

I can assure you that no pension plans wants to take a huge write-off on a limited partnership structure. And while $375 million is a big sum, it’s not dramatically larger than the US$150 million that the highly-regulated and well run CDPQ wrote-off when Celsius went bankrupt in 2022.

What’s more risky? A single direct equity investment in the crypto space, or an allocation to a private debt fund that in turn lends that capital allocation to a few dozen individual operating companies? Even if 100% of those companies were in the crypto space, the prospects of recovery would be higher, whether or not the private debt fund (the so-called “shadow bank”) itself is regulated. That’s just the nature of secured lending, and you can’t regulate away poor management decisions.

Unlike in the case of AIG or Lehman Brothers, where derivatives and swaps tied hundreds of institutions together, often unknowingly, the loss of a $5 billion debt fund is highly contained. Despite being highly-regulated, AIG required an US$85 billion bailout in September 2008; what scenario would have to arise that might necessitate a government bailout of a large private debt fund? Even for 10% of that amount? And please “show your work,” as Joe Hocevar, my Grade Seven math teacher, would say.

The growth of the private debt market has contributed hundreds of billions of dollars of growth capital to operating businesses the world over. Whether that’s on better terms or at a worse price than what commercial banks have to offer is a red herring. Even the Bank of Canada notes that, on a relative basis, commercial bank lending has grown faster in recent years:

NBFI’s share of outstanding credit has either declined or remained steady since the global financial crisis. This implies that other players such as traditional deposit-taking institutions and long-term institutional investors have provided credit at an even faster pace.

The final concern about the growth of the Private Debt market is a weird one, and goes something like this: private companies and individuals have come to rely on private credit, and what if that availability of capital goes away down the road?

Non-bank financial intermediation entities are a valuable alternative source of credit to the Canadian economy. However, they are exempt from prudential regulation, making them more vulnerable to a build-up of risks. If Canadian households and businesses rely increasingly on NBFI financing, it could raise concerns about their access to credit in times of stress.

Good question. I can appreciate how that would impact a country’s economic growth prospects, but I don’t see how the systemic risk to the financial system would increase if the private debt market shrank. Moreover, in times of stress, commercial banks tend to pull back; where’s the concern about that reality? I thought Regulators wanted banks to pull back when the global economy is at risk, explaining why OSFI just boosted the banking industry’s capital ratios: a step that will reduce traditional bank lending to many individuals and businesses, while increasing the cost of capital for others.

Until Bank Governors and Columnists can lay out the tangible potential global systemic risk represented by the Private Credit sector, perhaps they should drop the shady talk.

MRM

(this post, like all blogs, is an Opinion Piece)

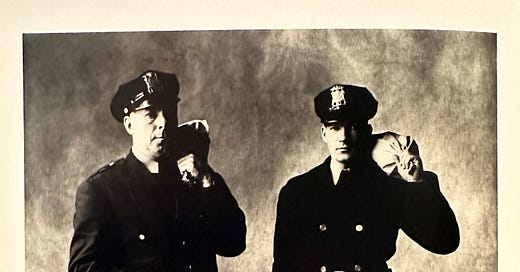

(photo: Money Truck Guards, New York, 1951, by Irving Penn)

This is a good piece. However, as a pension beneficiary and not an investor, I find that the trend of our pension funds significantly expanding their allocations in private credit could intensify existing problems of inadequate transparency and a lack of regulatory attention. Our Ontario funds don't seem to even feel obligated to properly disclose their private assets, and conflicts are typically disclosed only inadvertently. While the potential losses may not reach the systemic risk scale that you reference, these issues, although ultimately containable and manageable, regulators and beneficiaries may never get the full story.